Transforming Communities Through Education: The Story of DIL

Across Pakistan, tens of thousands of children—especially girls—continue to face obstacles to accessing quality education, shaped by poverty, distance, and deeply rooted social norms. For nearly three decades, the Development in Literacy (DIL) has worked to break down these barriers in underserved regions.

This feature explores how DIL’s work is not only expanding access to education but also reshaping attitudes and possibilities within the communities it serves.

Societal Resistance & Change

Even today, in parts of Pakistan, sending girls to school can carry serious social risks, from backlash to early marriage. In certain communities, families once feared the consequences of girls attending school.

“In certain schools in Balochistan, mothers would send their daughters to school when the father was away. When one father came home early and found his daughter at school, he burnt her books and beat his wife. Now, those same fathers are the ones who bring the girls to school themselves.”

— Fiza Shah, CEO & Founder - Developments in Literacy (DIL)

DIL’s work has helped shift these attitudes, showing families the tangible benefits of education and increasing opportunities for girls across rural Pakistan.

Journey of DIL: From Small Beginnings to National Impact

Born in Quetta, Fiza Shah founded DIL in 1997 with a vision to create learning opportunities for underprivileged children. What began as a modest 10-school project in Mianwali has evolved into a nationwide organization, serving nearly 90,000 students across Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT).

Over the years, DIL has expanded its programs from primary education to matric-level schools, introduced life skills and university preparation programs, and implemented innovative teaching methods to improve student outcomes. The organization also prioritizes inclusive, gender-responsive classrooms, ensuring that every child—regardless of background—has access to quality education.

DIL’s Reach Across Pakistan

90,000

Student Served

214

Students Across Pakistan

78%

Government-Adopted Schools

DIL’s impact is perhaps most visible in the lives of girls who have overcome social barriers to pursue education and careers.

How DIL Students Are Changing Their Communities

Alumni Spotlight – Afreen Mushtaq (Harvard Graduate)

From Orangi Town, Afreen spent 12 years at DIL School, earning a full scholarship to IBA and later becoming a Fulbright Scholar at Harvard. She is a vocal advocate for girls’ education, featured among Pakistan’s 25 most influential young women, and has delivered a TED Talk that inspires communities nationwide.

Afshan Bhutto (Khairpur, Sindh)

Born into a modest family in Kairpur, Afshan Bhutto began her educational journey at DIL School, where technology-enabled active learning shaped her ambitions. Encouraged by the institute’s support, she pursued a career in the IT industry. Today, working remotely from her home for a UK-based IT company, she supports her family and turns her aspirations into reality—an example of how access to quality education can illuminate a path to a brighter future.

These stories demonstrate how education can empower girls to challenge societal norms and become change-makers in their communities.

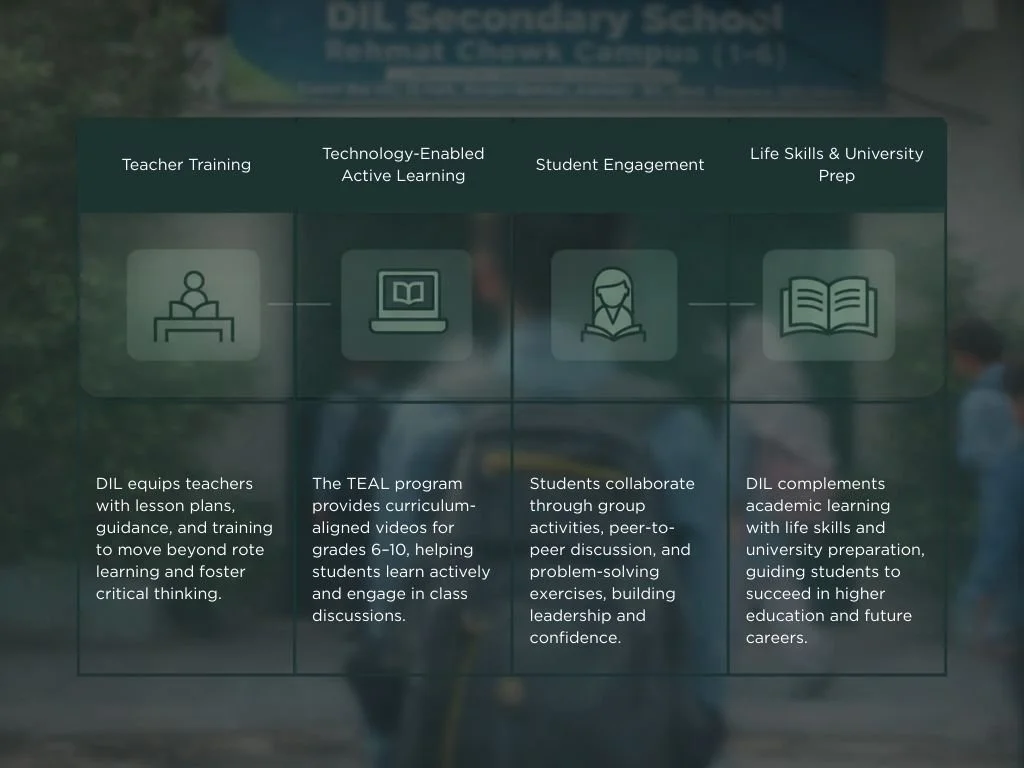

To reshape classrooms and strengthen learning outcomes, DIL equips teachers with structured guidance, lesson plans, and modern tools. Traditional rote memorization is replaced by interactive, student-centered approaches that cultivate critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving.

Transforming Classrooms and Learning

The Technology-Enabled Academic Learning (TEAL) program introduces curriculum-aligned videos into grades 6–10 classrooms. Students watch videos, discuss concepts, and participate in problem-solving exercises—shifting responsibility for learning to the students, while teachers guide and facilitate.

Classrooms now feature group activities, peer-to-peer discussions, and leadership development exercises. Children learn to articulate ideas, work collaboratively, and take ownership of their learning. These methods have increased student engagement, confidence, and academic performance while giving teachers the tools to foster meaningful learning experiences.

Leveraging Technology and AI

Looking ahead, DIL is integrating AI and Learning Management Systems (LMS) to enhance learning outcomes. Each student in grades 9–10 receives a Chromebook, while AI-driven tools track student progress, provide feedback, and monitor teacher performance.

“AI is there, it’s not going away. If we don’t start using it properly, we will never get caught up. We’ll always be running behind.”

— Fiza Shah, CEO & Founder - Developments in Literacy (DIL)

This technology complements TEAL and teacher training programs, enabling DIL to scale innovative education across both private and government schools efficiently.

Global Support Fueling Local Impact

DIL operates with donors from Pakistan, the UK, US, Canada, and Hong Kong. Volunteers sustain operations worldwide, ensuring transparency and maximizing resources. Funds are dedicated directly to students, making DIL a model of effective NGO governance.

By 2030, DIL aims to extend its reach and impact, positioning education as a driver of social mobility and community development. The focus is on widening access to learning, strengthening institutional capacity, and ensuring students are equipped to meet the demands of a rapidly changing world. At the heart of the vision is a commitment to empowering communities through education.

Future Goals and Vision

90,000

students reached today

500,000

Target by 2030

Join DIL in transforming lives through education. Support girls’ learning, help schools thrive, and empower the next generation of leaders. https://www.dil.org/donate